Volume 23, Number 12—December 2017

CME ACTIVITY - Research

Group B Streptococcus Infections Caused by Improper Sourcing and Handling of Fish for Raw Consumption, Singapore, 2015–2016

Figure 3

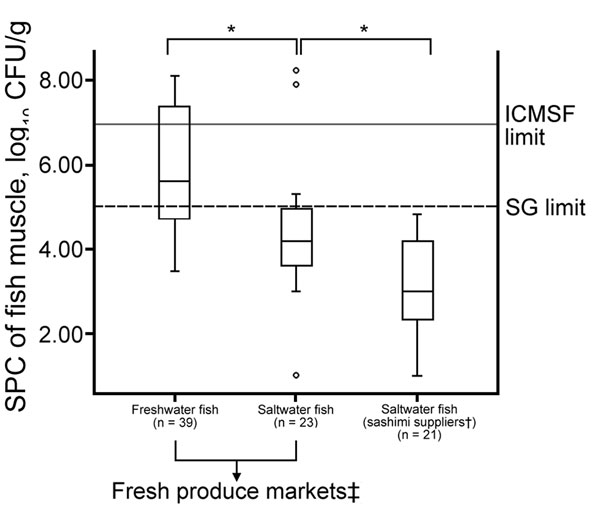

Figure 3. SPCs for fish samples (muscle) collected from fresh produce markets during investigation of group B Streptococcus infections, Singapore, 2015–2016. Solid horizontal line indicates ICMSF limit for SPCs in fresh fish intended for cooking (<7 log10 CFU/g) (23). Dashed horizontal line indicates Singapore regulatory limit for SPCs for ready-to-eat foods (<5 log10 CFU/g) (14). Top and bottom of boxes in plots indicate 25th and 75th percentiles, horizontal lines indicate medians, and whiskers indicate minimum and maximum values. Open circles indicate outliers. *p<0.05. †Companies that supplied sashimi grade fish to restaurants and snack bars. ‡Fish stalls at ports and wet markets, as well as fresh produce sections of supermarkets, excluding sashimi and sushi counters of supermarkets. ICMSF, International Commission on Microbiological Specifications of Foods; SG, Singapore government; SPCs, standard plate counts.

References

- Joint news release between the Ministry of Health Singapore (MOH) and the Agri-Food and Veterinary Authority of Singapore (AVA) and the National Environment Agency (NEA). Update on investigation into group B Streptococcus cases. July 24, 2015 [cited 2016 Aug 10]. http://www.nea.gov.sg/corporate-functions/newsroom/news-releases/year/2015/month/7/category/food-hygiene/update-on-investigation-into-group-b-streptococcus-cases

- Tan S, Lin Y, Foo K, Koh HF, Tow C, Zhang Y, et al. Group B Streptococcus serotype III sequence type 283 bacteremia associated with consumption of raw fish, Singapore. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22:1970–3. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Rajendram P, Mar Kyaw W, Leo YS, Ho H, Chen WK, Lin R, et al. Group B Streptococcus sequence type 283 disease linked to consumption of raw fish, Singapore. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22:1974–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Tan K, Wijaya L, Chiew HJ, Sitoh YY, Shafi H, Chen RC, et al. Diffusion-weighted MRI abnormalities in an outbreak of Streptococcus agalactiae Serotype III, multilocus sequence type 283 meningitis. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2017;45:507–14. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Manning SD, Neighbors K, Tallman PA, Gillespie B, Marrs CF, Borchardt SM, et al. Prevalence of group B streptococcus colonization and potential for transmission by casual contact in healthy young men and women. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:380–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Streptococcus agalactiae: pathogen safety data sheet—infectious substances. April 30, 2012 [cited 2016 Aug 10]. http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/lab-bio/res/psds-ftss/streptococcus-agalactiae-eng.php

- Ballard MS, Schønheyder HC, Knudsen JD, Lyytikäinen O, Dryden M, Kennedy KJ, et al.; International Bacteremia Surveillance Collaborative. The changing epidemiology of group B streptococcus bloodstream infection: a multi-national population-based assessment. Infect Dis (Lond). 2016;48:386–91. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Phares CR, Lynfield R, Farley MM, Mohle-Boetani J, Harrison LH, Petit S, et al.; Active Bacterial Core surveillance/Emerging Infections Program Network. Epidemiology of invasive group B streptococcal disease in the United States, 1999-2005. JAMA. 2008;299:2056–65. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Foxman B, Gillespie BW, Manning SD, Marrs CF. Risk factors for group B streptococcal colonization: potential for different transmission systems by capsular type. Ann Epidemiol. 2007;17:854–62. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Delannoy CM, Crumlish M, Fontaine MC, Pollock J, Foster G, Dagleish MP, et al. Human Streptococcus agalactiae strains in aquatic mammals and fish. BMC Microbiol. 2013;13:41. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Ip M, Cheuk ES, Tsui MH, Kong F, Leung TN, Gilbert GL. Identification of a Streptococcus agalactiae serotype III subtype 4 clone in association with adult invasive disease in Hong Kong. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:4252–4. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kalimuddin S, Chen SL, Lim CTK, Koh TH, Tan TY, Kam M, et al. Singapore Group B Streptococcus Consortium. 2015 epidemic of severe Streptococcus agalactiae ST283 infections in Singapore associated with the consumption of raw freshwater fish: a detailed analysis of clinical, epidemiological and bacterial sequencing data. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64(Suppl_2):S145–52.

- Joint news release between the Agri-Food and Veterinary Authority of Singapore (AVA) and the Ministry of Health Singapore (MOH) and the National Environment Agency (NEA). Freshwater fish banned from ready-to-eat raw fish dishes. December 5, 2015 [cited 2016 Aug 10]. http://www.nea.gov.sg/corporate-functions/newsroom/news-releases/freshwater-fish-banned-from-ready-to-eat-raw-fish-dishes

- Agri-Food and Veterinary Authority of Singapore. Sale of food act, chapter 283, section 56 (1), food regulations. December 20, 2016 [cited 2017 Jan 9]. http://www.ava.gov.sg/legislation

- British Columbia Centre for Disease Control. Food processing plants: guideline for live retail fish holding system. November 2013 [cited 2016 Aug 17]. http://www.bccdc.ca/resource-gallery/Documents/Educational%20Materials/EH/FPS/Food/RetailFishHoldingTankGuidelines_Nov2013trs.pdf

- Da Cunha V, Davies MR, Douarre PE, Rosinski-Chupin I, Margarit I, Spinali S, et al.; DEVANI Consortium. Streptococcus agalactiae clones infecting humans were selected and fixed through the extensive use of tetracycline. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4544. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Mehershahi KS, Hsu LY, Koh TH, Chen SL. Complete genome sequence of Streptococcus agalactiae serotype III, multilocus sequence type 283 strain SG-M1. Genome Announc. 2015;3:e01188–15.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Abuseliana AF, Daud HH, Aziz SA, Bejo SK, Alsaid M. Pathogenicity of Streptococcus agalactiae isolated from a fish farm in Selangor to juvenile red tilapia (Oreochromis sp.). J Anim Vet Adv. 2011;10:914–9. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Liu G, Zhang W, Lu C. Complete genome sequence of Streptococcus agalactiae GD201008-001, isolated in China from tilapia with meningoencephalitis. J Bacteriol. 2012;194:6653. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Wang R, Li L, Huang Y, Luo F, Liang W, Gan X, et al. Comparative genome analysis identifies two large deletions in the genome of highly-passaged attenuated Streptococcus agalactiae strain YM001 compared to the parental pathogenic strain HN016. BMC Genomics. 2015;16:897. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Martins C, Eding EH, Verdegem MC, Heinsbroek LT, Schneider O, Blancheton J-P, et al. New developments in recirculating aquaculture systems in Europe: a perspective on environmental sustainability. Aquacult Eng. 2010;43:83–93. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Little D, Edwards P. Integrated livestock-fish farming systems. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; 2003 [cited 2017 Aug 15]. http://www.fao.org/docrep/006/y5098e/y5098e00.htm

- International Commission on Microbiological Specifications for Foods. Micro-organisms in foods 2: sampling for microbiological analysis; principles and specific applications. 2nd ed. 1986 [cited 2016 Aug 11]. http://www.icmsf.org/pdf/icmsf2.pdf

- Food and Drug Administration. Bad bug book: foodborne pathogenic microorganisms and natural toxins. 2nd ed. Silver Spring (MD): The Administration; 2012.

- Chau ML, Aung KT, Hapuarachchi HC, Lee PSV, Lim PY, Kang JSL, et al. Microbial survey of ready-to-eat salad ingredients sold at retail reveals the occurrence and the persistence of Listeria monocytogenes Sequence Types 2 and 87 in pre-packed smoked salmon. BMC Microbiol. 2017;17:46. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

1These authors contributed equally to this article.