Volume 29, Number 5—May 2023

Dispatch

Fatal Case of Heartland Virus Disease Acquired in the Mid-Atlantic Region, United States

Abstract

Heartland virus (HRTV) disease is an emerging tickborne illness in the midwestern and southern United States. We describe a reported fatal case of HRTV infection in the Maryland and Virginia region, states not widely recognized to have human HRTV disease cases. The range of HRTV could be expanding in the United States.

Heartland virus (HRTV) is a bandavirus spread by Amblyomma americanum (lone star) ticks in the midwestern and southern United States (1). Many cases of HRTV infection have been characterized by severe illness or death, mostly among men >50 years of age with multiple underlying conditions (1–7). HRTV infection in humans typically manifests as a nonspecific febrile illness characterized by malaise, myalgias, arthralgias, and gastrointestinal distress, along with thrombocytopenia, leukopenia, hyponatremia, and elevated liver transaminases (3). Most reported hospitalized patients recover, but deaths have occurred and have been associated with secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) (4,5).

Since HRTV was discovered in 2009 in Missouri, USA, human HRTV disease cases have also been reported in Kansas, Oklahoma, Arkansas, Tennessee, Kentucky, Indiana, Illinois, Iowa, Georgia, Pennsylvania, New York, and North Carolina according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC; https://www.cdc.gov/heartland-virus/statistics/index.html). Studies have documented HRTV RNA in A. americanum ticks and HRTV-neutralizing antibodies in vertebrate animals in these states (8–13). However, the distribution of A. americanum ticks is wider and growing, possibly because of climate change, which could lead to HRTV range expansion (3,11). Of note, vertebrate animals with neutralizing antibodies to HRTV have been documented in states without confirmed human cases, including Texas, Florida, South Carolina, and Louisiana in the south and Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine in the northeast (12,13). To date, no seropositive animals have been reported from Maryland or Virginia in the mid-Atlantic region. We describe a fatal human case of HRTV infection with secondary HLH in which initial infection likely occurred in either Maryland or Virginia.

The patient was a man in his late 60s who had a medical history of splenectomy from remote trauma, coronary artery disease, and hypertension. He was seen at an emergency department in November 2021 for 5 days of fever, nonbloody diarrhea, dyspnea, myalgias, and malaise. At initial examination, he appeared fatigued but was alert and oriented. Laboratory results were notable for hyponatremia, mildly elevated liver enzymes, leukopenia, and thrombocytopenia (Table). The patient had homes in rural areas of Maryland and Virginia and had not traveled outside of this area in the previous 3 months. He spent time outdoors on his properties but did not recall attached ticks or tick bites. Despite the lack of known tick bites, the symptom constellation and potential exposure led clinicians to highly suspect tickborne illness; they prescribed doxycycline and discharged the patient home.

Two days later, on day 7 after symptom onset, the patient returned to the emergency department with confusion, an unsteady gait, and new fecal and urinary incontinence; he was admitted for inpatient management. He had progressive encephalopathy with hyponatremia and rising transaminases (Table). Results of neurologic workup and imaging were unremarkable (Table). Computed tomography imaging of the abdomen and pelvis showed new pelvic and inguinal lymphadenopathy. The patient was treated with hypertonic saline, intravenous doxycycline, and piperacillin/tazobactam.

Because of clinical deterioration, he was transferred to a tertiary care center. At arrival at the tertiary center, he was fatigued and disoriented. Physical examination demonstrated new hepatomegaly and lower extremity livedo reticularis. Results of broad testing for infectious etiologies was negative (Appendix Table). Laboratory results demonstrated increased creatine kinase (9,567 U/L), lactate (2.5 mg/dL), lactate dehydrogenase (1,709 U/L), and ferritin (47,445 ng/mL). Interleukin 2 receptor, a marker for HLH, was also elevated (9,390 pg/mL) (Table). Immunosuppressive agents for management of likely secondary HLH were deferred while clinicians conducted a diagnostic work-up of the underlying disease process. An arboviral disease was the leading diagnostic consideration, but limited availability of commercial diagnostic testing for tickborne diseases delayed diagnosis.

The patient’s clinical course continued to deteriorate. He had acute respiratory failure, renal failure, and a cardiac arrest. He was transitioned to comfort care and died on day 13 after symptom onset.

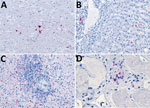

Because of concern for arboviral illness, the Virginia Department of Health (VDH) initiated an investigation and sent a serum specimen to CDC for testing (Appendix). Quantitative reverse transcription PCR was notably positive for HRTV RNA (Appendix Table). Autopsy findings identified markedly congested accessory spleens with abundant histiocytes, phagocytosing erythrocytes, and pulmonary hyperinflammation (Figure 1). Immunohistochemistry testing of heart, spleen, kidney, and liver samples were positive for HRTV at CDC (Figure 2). Immunohistochemistry of the spleen was negative for Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) at the clinical institution. The autopsy report concluded that the cause of death was respiratory failure secondary to hyperinflammation due to HLH, likely triggered by HRTV infection.

VDH performed tick drags at the patient’s 2 properties in eastern Maryland and central Virginia during early- to mid-June 2022. VDH collected a total of 193 ticks across the properties, which were sent to CDC for testing (Appendix). The tick pools collected from both properties tested negative for HRTV RNA.

HRTV disease has been reported in >50 patients in states across the midwestern and southern United States (1–7). A bite from an A. americanum tick is the only known means of environmental HRTV transmission (1). Corresponding to A. americanum tick seasonal activity, all reported cases have occurred during April–September, and symptoms developed during June in most case-patients (1,3). Because the incubation period for HRTV is estimated to be 2 weeks, this patient was likely infected in late October. Adult ticks are minimally active at that time; however, larval ticks can become infected with HRTV and can still be observed during October (1,14). We suspect this patient was bitten by larval ticks unknowingly because of their small size, and that the bite marks healed before his clinical signs and symptoms appeared.

Maryland and Virginia fall within the A. americanum tick distribution area, but we found no previous reports of HRTV illness from those states during a literature search, and CDC had no reported cases from those states. Among 193 ticks collected during tick drags of both properties, no HRTV-infected vectors were found, but this result does not exclude HRTV in either state. Previous studies report low overall minimum infection rates among A. americanum ticks from other states, ranging from 0.4 to 11/1,000 ticks (1 infected tick/90–2,174 collected) (1,8,10,11). We suspect the Virginia property was the likely location of infection, based on the number of ticks VDH collected while sampling an area that the patient frequented 10–14 days before symptom onset and because fewer ticks were collected from the Maryland property (Appendix).

The patient’s clinical and laboratory findings were consistent with HLH secondary to HRTV infection. HLH has been documented in several cases of infection with the related Bandavirus, severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus, and in at least 1 case of HRTV infection (1,4). Reports showed corticosteroids and ribavirin did not effectively treat severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome–triggered HLH, but preliminary clinical data shows potential benefit from favipiravir (1,15). Currently, clinical management for HRTV infection is supportive care (3).

We hypothesize that HRTV infection is underrecognized and mainly diagnosed when severe disease leads to additional testing at referral centers. Although lack of responsiveness to appropriate antimicrobial agents for bacterial tickborne illness might suggest severe disease (2), self-limited disease likely is undiagnosed or diagnosed as another tickborne disease. Because tick ranges are increasing overall, incidence of previously regional tickborne infections, such as HRTV, likely will continue to increase. Expanding testing capabilities for arbovirus and tickborne infections, including multiplex testing, would enable real-time assessment and management of patients with potential arboviral and other tickborne infections.

Dr. Liu is an infectious disease fellow at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, USA. His research interest is in local, targeted antimicrobial therapy. Mr. Kannan is an MD candidate at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine and a PhD candidate in the Johns Hopkins Department of Biomedical Engineering, Baltimore, Maryland, USA. His research interests include internal medicine and the interface of evidence-based medicine and patient-centered decision-making.

Acknowledgment

We thank the patient’s family for their kindness with this study. We also thank Luciana Silva-Flannery for performing immunohistochemistry for HRTV, and the manuscript’s anonymous reviewers.

References

- Brault AC, Savage HM, Duggal NK, Eisen RJ, Staples JE. Heartland virus epidemiology, vector association, and disease potential. Viruses. 2018;10:1–17. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- McMullan LK, Folk SM, Kelly AJ, MacNeil A, Goldsmith CS, Metcalfe MG, et al. A new phlebovirus associated with severe febrile illness in Missouri. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:834–41. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Staples JE, Pastula DM, Panella AJ, Rabe IB, Kosoy OI, Walker WL, et al. Investigation of heartland virus disease throughout the United States, 2013–2017. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2020;7:a125. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Carlson AL, Pastula DM, Lambert AJ, Staples JE, Muehlenbachs A, Turabelidze G, et al. Heartland virus and hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in immunocompromised patient, Missouri, USA. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018;24:893–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Fill MA, Compton ML, McDonald EC, Moncayo AC, Dunn JR, Schaffner W, et al. Novel clinical and pathologic findings in a heartland virus-associated death. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64:510–2.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Muehlenbachs A, Fata CR, Lambert AJ, Paddock CD, Velez JO, Blau DM, et al. Heartland virus-associated death in tennessee. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:845–50. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Decker MD, Morton CT, Moncayo AC. One confirmed and 2 suspected cases of heartland virus disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:3237–40. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Dupuis AP II, Prusinski MA, O’Connor C, Maffei JG, Ngo KA, Koetzner CA, et al. Heartland virus transmission, Suffolk County, New York, USA. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021;27:3128–32. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Newman BC, Sutton WB, Moncayo AC, Hughes HR, Taheri A, Moore TC, et al. Heartland virus in lone star ticks, Alabama, USA. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26:1954–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Romer Y, Adcock K, Wei Z, Mead DG, Kirstein O, Bellman S, et al. Isolation of heartland virus from lone star ticks, Georgia, USA, 2019. Emerg Infect Dis. 2022;28:786–92. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Tuten HC, Burkhalter KL, Noel KR, Hernandez EJ, Yates S, Wojnowski K, et al. Heartland virus in humans and ticks, Illinois, USA, 2018–2019. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26:1548–52. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Clarke LL, Ruder MG, Mead DG, Howerth EW. Heartland virus exposure in white-tailed deer in the Southeastern United States, 2001–2015. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2018;99:1346–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Riemersma KK, Komar N. Heartland virus neutralizing antibodies in vertebrate wildlife, United States, 2009–2014. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21:1830–3. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Jackson LK, Gaydon DM, Goddard J. Seasonal activity and relative abundance of Amblyomma americanum in Mississippi. J Med Entomol. 1996;33:128–31. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Suemori K, Saijo M, Yamanaka A, Himeji D, Kawamura M, Haku T, et al. A multicenter non-randomized, uncontrolled single arm trial for evaluation of the efficacy and the safety of the treatment with favipiravir for patients with severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2021;15:

e0009103 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

Figures

Table

Cite This ArticleOriginal Publication Date: February 23, 2023

1These first authors contributed equally to this article.

Table of Contents – Volume 29, Number 5—May 2023

| EID Search Options |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Please use the form below to submit correspondence to the authors or contact them at the following address:

Christopher J. Hoffmann, Johns Hopkins University, 1550 Orleans St, CRBII 1M11, Baltimore, MD 21205, USA

Top