Hard disk drive

Electro-mechanical data storage device From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Electro-mechanical data storage device From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

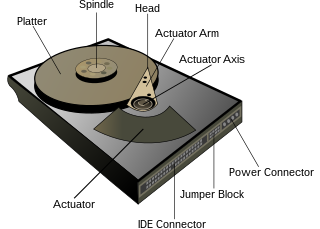

A hard disk drive (HDD), hard disk, hard drive, or fixed disk[a] is an electro-mechanical data storage device that stores and retrieves digital data using magnetic storage with one or more rigid rapidly rotating platters coated with magnetic material. The platters are paired with magnetic heads, usually arranged on a moving actuator arm, which read and write data to the platter surfaces.[1] Data is accessed in a random-access manner, meaning that individual blocks of data can be stored and retrieved in any order. HDDs are a type of non-volatile storage, retaining stored data when powered off.[2][3][4] Modern HDDs are typically in the form of a small rectangular box.

Hard disk drives were introduced by IBM in 1956,[5] and were the dominant secondary storage device for general-purpose computers beginning in the early 1960s. HDDs maintained this position into the modern era of servers and personal computers, though personal computing devices produced in large volume, like mobile phones and tablets, rely on flash memory storage devices. More than 224 companies have produced HDDs historically, though after extensive industry consolidation, most units are manufactured by Seagate, Toshiba, and Western Digital. HDDs dominate the volume of storage produced (exabytes per year) for servers. Though production is growing slowly (by exabytes shipped[6]), sales revenues and unit shipments are declining, because solid-state drives (SSDs) have higher data-transfer rates, higher areal storage density, somewhat better reliability,[7][8] and much lower latency and access times.[9][10][11][12]

The revenues for SSDs, most of which use NAND flash memory, slightly exceeded those for HDDs in 2018.[13] Flash storage products had more than twice the revenue of hard disk drives as of 2017[update].[14] Though SSDs have four to nine times higher cost per bit,[15][16] they are replacing HDDs in applications where speed, power consumption, small size, high capacity and durability are important.[11][12] As of 2019[update], the cost per bit of SSDs is falling, and the price premium over HDDs has narrowed.[16]

The primary characteristics of an HDD are its capacity and performance. Capacity is specified in unit prefixes corresponding to powers of 1000: a 1-terabyte (TB) drive has a capacity of 1,000 gigabytes, where 1 gigabyte = 1 000 megabytes = 1 000 000 kilobytes (1 million) = 1 000 000 000 bytes (1 billion). Typically, some of an HDD's capacity is unavailable to the user because it is used by the file system and the computer operating system, and possibly inbuilt redundancy for error correction and recovery. There can be confusion regarding storage capacity since capacities are stated in decimal gigabytes (powers of 1000) by HDD manufacturers, whereas the most commonly used operating systems report capacities in powers of 1024, which results in a smaller number than advertised. Performance is specified as the time required to move the heads to a track or cylinder (average access time), the time it takes for the desired sector to move under the head (average latency, which is a function of the physical rotational speed in revolutions per minute), and finally, the speed at which the data is transmitted (data rate).

The two most common form factors for modern HDDs are 3.5-inch, for desktop computers, and 2.5-inch, primarily for laptops. HDDs are connected to systems by standard interface cables such as SATA (Serial ATA), USB, SAS (Serial Attached SCSI), or PATA (Parallel ATA) cables.

A partially disassembled IBM 350 hard disk drive (RAMAC) | |

| Date invented | December 24, 1954[b] |

|---|---|

| Invented by | IBM team led by Rey Johnson |

| Parameter | Started with (1957) | Improved to | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Capacity (formatted) | 3.75 megabytes[18] | 32 terabytes (as of 2024[update])[19][20] | 8.5-million-to-one[c] |

| Physical volume | 68 cubic feet (1.9 m3)[d][5] | 2.1 cubic inches (34 cm3)[21][e] | 56,000-to-one[f] |

| Weight | 2,000 pounds (910 kg)[5] | 2.2 ounces (62 g)[21] | 15,000-to-one[g] |

| Average access time | approx. 600 milliseconds[5] | 2.5 ms to 10 ms; RW RAM dependent | about 200-to-one[h] |

| Price | US$9,200 per megabyte (1961;[22] US$97,500 in 2022) | US$14.4 per terabyte by end of 2022[23] | 6.8-billion-to-one[i] |

| Data density | 2,000 bits per square inch[24] | 1.4 terabits per square inch in 2023[25] | 700-million-to-one[j] |

| Average lifespan | c. 2000 hrs MTBF[citation needed] | c. 2,500,000 hrs (~285 years) MTBF[26] | 1250-to-one[k] |

The first production IBM hard disk drive, the 350 disk storage, shipped in 1957 as a component of the IBM 305 RAMAC system. It was approximately the size of two large refrigerators and stored five million six-bit characters (3.75 megabytes)[18] on a stack of 52 disks (100 surfaces used).[27] The 350 had a single arm with two read/write heads, one facing up and the other down, that moved both horizontally between a pair of adjacent platters and vertically from one pair of platters to a second set.[28][29][30] Variants of the IBM 350 were the IBM 355, IBM 7300 and IBM 1405.

In 1961, IBM announced, and in 1962 shipped, the IBM 1301 disk storage unit,[31] which superseded the IBM 350 and similar drives. The 1301 consisted of one (for Model 1) or two (for model 2) modules, each containing 25 platters, each platter about 1⁄8-inch (3.2 mm) thick and 24 inches (610 mm) in diameter.[32] While the earlier IBM disk drives used only two read/write heads per arm, the 1301 used an array of 48[l] heads (comb), each array moving horizontally as a single unit, one head per surface used. Cylinder-mode read/write operations were supported, and the heads flew about 250 micro-inches (about 6 μm) above the platter surface. Motion of the head array depended upon a binary adder system of hydraulic actuators which assured repeatable positioning. The 1301 cabinet was about the size of three large refrigerators placed side by side, storing the equivalent of about 21 million eight-bit bytes per module. Access time was about a quarter of a second.

Also in 1962, IBM introduced the model 1311 disk drive, which was about the size of a washing machine and stored two million characters on a removable disk pack. Users could buy additional packs and interchange them as needed, much like reels of magnetic tape. Later models of removable pack drives, from IBM and others, became the norm in most computer installations and reached capacities of 300 megabytes by the early 1980s. Non-removable HDDs were called "fixed disk" drives.

In 1963, IBM introduced the 1302,[33] with twice the track capacity and twice as many tracks per cylinder as the 1301. The 1302 had one (for Model 1) or two (for Model 2) modules, each containing a separate comb for the first 250 tracks and the last 250 tracks.

Some high-performance HDDs were manufactured with one head per track, e.g., Burroughs B-475 in 1964, IBM 2305 in 1970, so that no time was lost physically moving the heads to a track and the only latency was the time for the desired block of data to rotate into position under the head.[34] Known as fixed-head or head-per-track disk drives, they were very expensive and are no longer in production.[35]

In 1973, IBM introduced a new type of HDD code-named "Winchester". Its primary distinguishing feature was that the disk heads were not withdrawn completely from the stack of disk platters when the drive was powered down. Instead, the heads were allowed to "land" on a special area of the disk surface upon spin-down, "taking off" again when the disk was later powered on. This greatly reduced the cost of the head actuator mechanism but precluded removing just the disks from the drive as was done with the disk packs of the day. Instead, the first models of "Winchester technology" drives featured a removable disk module, which included both the disk pack and the head assembly, leaving the actuator motor in the drive upon removal. Later "Winchester" drives abandoned the removable media concept and returned to non-removable platters.

In 1974, IBM introduced the swinging arm actuator, made feasible because the Winchester recording heads function well when skewed to the recorded tracks. The simple design of the IBM GV (Gulliver) drive,[36] invented at IBM's UK Hursley Labs, became IBM's most licensed electro-mechanical invention[37] of all time, the actuator and filtration system being adopted in the 1980s eventually for all HDDs, and still universal nearly 40 years and 10 billion arms later.

Like the first removable pack drive, the first "Winchester" drives used platters 14 inches (360 mm) in diameter. In 1978, IBM introduced a swing arm drive, the IBM 0680 (Piccolo), with eight-inch platters, exploring the possibility that smaller platters might offer advantages. Other eight-inch drives followed, then 5+1⁄4 in (130 mm) drives, sized to replace the contemporary floppy disk drives. The latter were primarily intended for the then fledgling personal computer (PC) market.

Over time, as recording densities were greatly increased, further reductions in disk diameter to 3.5" and 2.5" were found to be optimum. Powerful rare earth magnet materials became affordable during this period and were complementary to the swing arm actuator design to make possible the compact form factors of modern HDDs.

As the 1980s began, HDDs were a rare and very expensive additional feature in PCs, but by the late 1980s, their cost had been reduced to the point where they were standard on all but the cheapest computers.

Most HDDs in the early 1980s were sold to PC end users as an external, add-on subsystem. The subsystem was not sold under the drive manufacturer's name but under the subsystem manufacturer's name such as Corvus Systems and Tallgrass Technologies, or under the PC system manufacturer's name such as the Apple ProFile. The IBM PC/XT in 1983 included an internal 10 MB HDD, and soon thereafter, internal HDDs proliferated on personal computers.

External HDDs remained popular for much longer on the Apple Macintosh. Many Macintosh computers made between 1986 and 1998 featured a SCSI port on the back, making external expansion simple. Older compact Macintosh computers did not have user-accessible hard drive bays (indeed, the Macintosh 128K, Macintosh 512K, and Macintosh Plus did not feature a hard drive bay at all), so on those models, external SCSI disks were the only reasonable option for expanding upon any internal storage.

HDD improvements have been driven by increasing areal density, listed in the table above. Applications expanded through the 2000s, from the mainframe computers of the late 1950s to most mass storage applications including computers and consumer applications such as storage of entertainment content.

In the 2000s and 2010s, NAND began supplanting HDDs in applications requiring portability or high performance. NAND performance is improving faster than HDDs, and applications for HDDs are eroding. In 2018, the largest hard drive had a capacity of 15 TB, while the largest capacity SSD had a capacity of 100 TB.[38] As of 2018[update], HDDs were forecast to reach 100 TB capacities around 2025,[39] but as of 2019[update], the expected pace of improvement was pared back to 50 TB by 2026.[40] Smaller form factors, 1.8-inches and below, were discontinued around 2010. The cost of solid-state storage (NAND), represented by Moore's law, is improving faster than HDDs. NAND has a higher price elasticity of demand than HDDs, and this drives market growth.[41] During the late 2000s and 2010s, the product life cycle of HDDs entered a mature phase, and slowing sales may indicate the onset of the declining phase.[42]

The 2011 Thailand floods damaged the manufacturing plants and impacted hard disk drive cost adversely between 2011 and 2013.[43]

In 2019, Western Digital closed its last Malaysian HDD factory due to decreasing demand, to focus on SSD production.[44] All three remaining HDD manufacturers have had decreasing demand for their HDDs since 2014.[45]

A modern HDD records data by magnetizing a thin film of ferromagnetic material[m] on both sides of a disk. Sequential changes in the direction of magnetization represent binary data bits. The data is read from the disk by detecting the transitions in magnetization. User data is encoded using an encoding scheme, such as run-length limited encoding,[n] which determines how the data is represented by the magnetic transitions.

A typical HDD design consists of a spindle that holds flat circular disks, called platters, which hold the recorded data. The platters are made from a non-magnetic material, usually aluminum alloy, glass, or ceramic. They are coated with a shallow layer of magnetic material typically 10–20 nm in depth, with an outer layer of carbon for protection.[47][48][49] For reference, a standard piece of copy paper is 0.07–0.18 mm (70,000–180,000 nm)[50] thick.

The platters in contemporary HDDs are spun at speeds varying from 4200 rpm in energy-efficient portable devices, to 15,000 rpm for high-performance servers.[52] The first HDDs spun at 1,200 rpm[5] and, for many years, 3,600 rpm was the norm.[53] As of November 2019[update], the platters in most consumer-grade HDDs spin at 5,400 or 7,200 rpm.

Information is written to and read from a platter as it rotates past devices called read-and-write heads that are positioned to operate very close to the magnetic surface, with their flying height often in the range of tens of nanometers. The read-and-write head is used to detect and modify the magnetization of the material passing immediately under it.

In modern drives, there is one head for each magnetic platter surface on the spindle, mounted on a common arm. An actuator arm (or access arm) moves the heads on an arc (roughly radially) across the platters as they spin, allowing each head to access almost the entire surface of the platter as it spins. The arm is moved using a voice coil actuator or, in some older designs, a stepper motor. Early hard disk drives wrote data at some constant bits per second, resulting in all tracks having the same amount of data per track, but modern drives (since the 1990s) use zone bit recording, increasing the write speed from inner to outer zone and thereby storing more data per track in the outer zones.

In modern drives, the small size of the magnetic regions creates the danger that their magnetic state might be lost because of thermal effects — thermally induced magnetic instability which is commonly known as the "superparamagnetic limit". To counter this, the platters are coated with two parallel magnetic layers, separated by a three-atom layer of the non-magnetic element ruthenium, and the two layers are magnetized in opposite orientation, thus reinforcing each other.[54] Another technology used to overcome thermal effects to allow greater recording densities is perpendicular recording (PMR), first shipped in 2005,[55] and as of 2007[update], used in certain HDDs.[56][57][58] Perpendicular recording may be accompanied by changes in the manufacturing of the read/write heads to increase the strength of the magnetic field created by the heads.[59]

In 2004, a higher-density recording media was introduced, consisting of coupled soft and hard magnetic layers. So-called exchange spring media magnetic storage technology, also known as exchange coupled composite media, allows good writability due to the write-assist nature of the soft layer. However, the thermal stability is determined only by the hardest layer and not influenced by the soft layer.[60][61]

Flux control MAMR (FC-MAMR) allows a hard drive to have increased recording capacity without the need for new hard disk drive platter materials. MAMR hard drives have a microwave-generating spin torque generator (STO) on the read/write heads which allows physically smaller bits to be recorded to the platters, increasing areal density. Normally hard drive recording heads have a pole called a main pole that is used for writing to the platters, and adjacent to this pole is an air gap and a shield. The write coil of the head surrounds the pole. The STO device is placed in the air gap between the pole and the shield to increase the strength of the magnetic field created by the pole; FC-MAMR technically doesn't use microwaves but uses technology employed in MAMR. The STO has a Field Generation Layer (FGL) and a Spin Injection Layer (SIL), and the FGL produces a magnetic field using spin-polarised electrons originating in the SIL, which is a form of spin torque energy.[62]

A typical HDD has two electric motors: a spindle motor that spins the disks and an actuator (motor) that positions the read/write head assembly across the spinning disks. The disk motor has an external rotor attached to the disks; the stator windings are fixed in place. Opposite the actuator at the end of the head support arm is the read-write head; thin printed-circuit cables connect the read-write heads to amplifier electronics mounted at the pivot of the actuator. The head support arm is very light, but also stiff; in modern drives, acceleration at the head reaches 550 g.

The actuator is a permanent magnet and moving coil motor that swings the heads to the desired position. A metal plate supports a squat neodymium–iron–boron (NIB) high-flux magnet. Beneath this plate is the moving coil, often referred to as the voice coil by analogy to the coil in loudspeakers, which is attached to the actuator hub, and beneath that is a second NIB magnet, mounted on the bottom plate of the motor (some drives have only one magnet).

The voice coil itself is shaped rather like an arrowhead and is made of doubly coated copper magnet wire. The inner layer is insulation, and the outer is thermoplastic, which bonds the coil together after it is wound on a form, making it self-supporting. The portions of the coil along the two sides of the arrowhead (which point to the center of the actuator bearing) then interact with the magnetic field of the fixed magnet. Current flowing radially outward along one side of the arrowhead and radially inward on the other produces the tangential force. If the magnetic field were uniform, each side would generate opposing forces that would cancel each other out. Therefore, the surface of the magnet is half north pole and half south pole, with the radial dividing line in the middle, causing the two sides of the coil to see opposite magnetic fields and produce forces that add instead of canceling. Currents along the top and bottom of the coil produce radial forces that do not rotate the head.

The HDD's electronics controls the movement of the actuator and the rotation of the disk and transfers data to or from a disk controller. Feedback of the drive electronics is accomplished by means of special segments of the disk dedicated to servo feedback. These are either complete concentric circles (in the case of dedicated servo technology) or segments interspersed with real data (in the case of embedded servo, otherwise known as sector servo technology). The servo feedback optimizes the signal-to-noise ratio of the GMR sensors by adjusting the voice coil motor to rotate the arm. A more modern servo system also employs milli or micro actuators to more accurately position the read/write heads.[63] The spinning of the disks uses fluid-bearing spindle motors. Modern disk firmware is capable of scheduling reads and writes efficiently on the platter surfaces and remapping sectors of the media that have failed.

Modern drives make extensive use of error correction codes (ECCs), particularly Reed–Solomon error correction. These techniques store extra bits, determined by mathematical formulas, for each block of data; the extra bits allow many errors to be corrected invisibly. The extra bits themselves take up space on the HDD, but allow higher recording densities to be employed without causing uncorrectable errors, resulting in much larger storage capacity.[64] For example, a typical 1 TB hard disk with 512-byte sectors provides additional capacity of about 93 GB for the ECC data.[65]

In the newest drives, as of 2009[update],[66] low-density parity-check codes (LDPC) were supplanting Reed–Solomon; LDPC codes enable performance close to the Shannon limit and thus provide the highest storage density available.[66][67]

Typical hard disk drives attempt to "remap" the data in a physical sector that is failing to a spare physical sector provided by the drive's "spare sector pool" (also called "reserve pool"),[68] while relying on the ECC to recover stored data while the number of errors in a bad sector is still low enough. The S.M.A.R.T (Self-Monitoring, Analysis and Reporting Technology) feature counts the total number of errors in the entire HDD fixed by ECC (although not on all hard drives as the related S.M.A.R.T attributes "Hardware ECC Recovered" and "Soft ECC Correction" are not consistently supported), and the total number of performed sector remappings, as the occurrence of many such errors may predict an HDD failure.

The "No-ID Format", developed by IBM in the mid-1990s, contains information about which sectors are bad and where remapped sectors have been located.[69]

Only a tiny fraction of the detected errors end up as not correctable. Examples of specified uncorrected bit read error rates include:

Within a given manufacturers model the uncorrected bit error rate is typically the same regardless of capacity of the drive.[70][71][72][73]

The worst type of errors are silent data corruptions which are errors undetected by the disk firmware or the host operating system; some of these errors may be caused by hard disk drive malfunctions while others originate elsewhere in the connection between the drive and the host.[74]

The rate of areal density advancement was similar to Moore's law (doubling every two years) through 2010: 60% per year during 1988–1996, 100% during 1996–2003 and 30% during 2003–2010.[76] Speaking in 1997, Gordon Moore called the increase "flabbergasting",[77] while observing later that growth cannot continue forever.[78] Price improvement decelerated to −12% per year during 2010–2017,[79] as the growth of areal density slowed. The rate of advancement for areal density slowed to 10% per year during 2010–2016,[80] and there was difficulty in migrating from perpendicular recording to newer technologies.[81]

As bit cell size decreases, more data can be put onto a single drive platter. In 2013, a production desktop 3 TB HDD (with four platters) would have had an areal density of about 500 Gbit/in2 which would have amounted to a bit cell comprising about 18 magnetic grains (11 by 1.6 grains).[82] Since the mid-2000s, areal density progress has been challenged by a superparamagnetic trilemma involving grain size, grain magnetic strength and ability of the head to write.[83] In order to maintain acceptable signal-to-noise, smaller grains are required; smaller grains may self-reverse (electrothermal instability) unless their magnetic strength is increased, but known write head materials are unable to generate a strong enough magnetic field sufficient to write the medium in the increasingly smaller space taken by grains.

Magnetic storage technologies are being developed to address this trilemma, and compete with flash memory–based solid-state drives (SSDs). In 2013, Seagate introduced shingled magnetic recording (SMR),[84] intended as something of a "stopgap" technology between PMR and Seagate's intended successor heat-assisted magnetic recording (HAMR). SMR utilizes overlapping tracks for increased data density, at the cost of design complexity and lower data access speeds (particularly write speeds and random access 4k speeds).[85][86]

By contrast, HGST (now part of Western Digital) focused on developing ways to seal helium-filled drives instead of the usual filtered air. Since turbulence and friction are reduced, higher areal densities can be achieved due to using a smaller track width, and the energy dissipated due to friction is lower as well, resulting in a lower power draw. Furthermore, more platters can be fit into the same enclosure space, although helium gas is notoriously difficult to prevent escaping.[87] Thus, helium drives are completely sealed and do not have a breather port, unlike their air-filled counterparts.

Other recording technologies are either under research or have been commercially implemented to increase areal density, including Seagate's heat-assisted magnetic recording (HAMR). HAMR requires a different architecture with redesigned media and read/write heads, new lasers, and new near-field optical transducers.[88] HAMR is expected to ship commercially in late 2024,[89] after technical issues delayed its introduction by more than a decade, from earlier projections as early as 2009.[90][91][92][93] HAMR's planned successor, bit-patterned recording (BPR),[94] has been removed from the roadmaps of Western Digital and Seagate.[95] Western Digital's microwave-assisted magnetic recording (MAMR),[96][97] also referred to as energy-assisted magnetic recording (EAMR), was sampled in 2020, with the first EAMR drive, the Ultrastar HC550, shipping in late 2020.[98][99][100] Two-dimensional magnetic recording (TDMR)[82][101] and "current perpendicular to plane" giant magnetoresistance (CPP/GMR) heads have appeared in research papers.[102][103][104]

Some drives have adopted dual independent actuator arms to increase read/write speeds and compete with SSDs.[105] A 3D-actuated vacuum drive (3DHD) concept[106] and 3D magnetic recording have been proposed.[107]

Depending upon assumptions on feasibility and timing of these technologies, Seagate forecasts that areal density will grow 20% per year during 2020–2034.[40]

The highest-capacity HDDs shipping commercially as of 2025[update] are 32 TB.[19][failed verification] The capacity of a hard disk drive, as reported by an operating system to the end user, is smaller than the amount stated by the manufacturer for several reasons, e.g. the operating system using some space, use of some space for data redundancy, space use for file system structures. Confusion of decimal prefixes and binary prefixes can also lead to errors.

Modern hard disk drives appear to their host controller as a contiguous set of logical blocks, and the gross drive capacity is calculated by multiplying the number of blocks by the block size. This information is available from the manufacturer's product specification, and from the drive itself through use of operating system functions that invoke low-level drive commands.[108][109] Older IBM and compatible drives, e.g. IBM 3390 using the CKD record format, have variable length records; such drive capacity calculations must take into account the characteristics of the records. Some newer DASD simulate CKD, and the same capacity formulae apply.

The gross capacity of older sector-oriented HDDs is calculated as the product of the number of cylinders per recording zone, the number of bytes per sector (most commonly 512), and the count of zones of the drive.[citation needed] Some modern SATA drives also report cylinder-head-sector (CHS) capacities, but these are not physical parameters because the reported values are constrained by historic operating system interfaces. The C/H/S scheme has been replaced by logical block addressing (LBA), a simple linear addressing scheme that locates blocks by an integer index, which starts at LBA 0 for the first block and increments thereafter.[110] When using the C/H/S method to describe modern large drives, the number of heads is often set to 64, although a typical modern hard disk drive has between one and four platters. In modern HDDs, spare capacity for defect management is not included in the published capacity; however, in many early HDDs, a certain number of sectors were reserved as spares, thereby reducing the capacity available to the operating system. Furthermore, many HDDs store their firmware in a reserved service zone, which is typically not accessible by the user, and is not included in the capacity calculation.

For RAID subsystems, data integrity and fault-tolerance requirements also reduce the realized capacity. For example, a RAID 1 array has about half the total capacity as a result of data mirroring, while a RAID 5 array with n drives loses 1/n of capacity (which equals to the capacity of a single drive) due to storing parity information. RAID subsystems are multiple drives that appear to be one drive or more drives to the user, but provide fault tolerance. Most RAID vendors use checksums to improve data integrity at the block level. Some vendors design systems using HDDs with sectors of 520 bytes to contain 512 bytes of user data and eight checksum bytes, or by using separate 512-byte sectors for the checksum data.[111]

Some systems may use hidden partitions for system recovery, reducing the capacity available to the end user without knowledge of special disk partitioning utilities like diskpart in Windows.[112]

Data is stored on a hard drive in a series of logical blocks. Each block is delimited by markers identifying its start and end, error detecting and correcting information, and space between blocks to allow for minor timing variations. These blocks often contained 512 bytes of usable data, but other sizes have been used. As drive density increased, an initiative known as Advanced Format extended the block size to 4096 bytes of usable data, with a resulting significant reduction in the amount of disk space used for block headers, error-checking data, and spacing.

The process of initializing these logical blocks on the physical disk platters is called low-level formatting, which is usually performed at the factory and is not normally changed in the field.[113] High-level formatting writes data structures used by the operating system to organize data files on the disk. This includes writing partition and file system structures into selected logical blocks. For example, some of the disk space will be used to hold a directory of disk file names and a list of logical blocks associated with a particular file.

Examples of partition mapping scheme include Master boot record (MBR) and GUID Partition Table (GPT). Examples of data structures stored on disk to retrieve files include the File Allocation Table (FAT) in the DOS file system and inodes in many UNIX file systems, as well as other operating system data structures (also known as metadata). As a consequence, not all the space on an HDD is available for user files, but this system overhead is usually small compared with user data.

| Capacity advertised by manufacturers[o] | Capacity expected by some consumers[p] | Reported capacity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Windows[p] | macOS ver 10.6+[o] | ||||

| With prefix | Bytes | Bytes | Diff. | ||

| 100 GB | 100,000,000,000 | 107,374,182,400 | 7.37% | 93.1 GB | 100 GB |

| 1 TB | 1,000,000,000,000 | 1,099,511,627,776 | 9.95% | 931 GB | 1,000 GB, 1,000,000 MB |

In the early days of computing, the total capacity of HDDs was specified in seven to nine decimal digits frequently truncated with the idiom millions.[116][33] By the 1970s, the total capacity of HDDs was given by manufacturers using SI decimal prefixes such as megabytes (1 MB = 1,000,000 bytes), gigabytes (1 GB = 1,000,000,000 bytes) and terabytes (1 TB = 1,000,000,000,000 bytes).[114][117][118][119] However, capacities of memory are usually quoted using a binary interpretation of the prefixes, i.e. using powers of 1024 instead of 1000.

Software reports hard disk drive or memory capacity in different forms using either decimal or binary prefixes. The Microsoft Windows family of operating systems uses the binary convention when reporting storage capacity, so an HDD offered by its manufacturer as a 1 TB drive is reported by these operating systems as a 931 GB HDD. Mac OS X 10.6 ("Snow Leopard") uses decimal convention when reporting HDD capacity.[120] The default behavior of the df command-line utility on Linux is to report the HDD capacity as a number of 1024-byte units.[121]

The difference between the decimal and binary prefix interpretation caused some consumer confusion and led to class action suits against HDD manufacturers. The plaintiffs argued that the use of decimal prefixes effectively misled consumers, while the defendants denied any wrongdoing or liability, asserting that their marketing and advertising complied in all respects with the law and that no class member sustained any damages or injuries.[122][123][124] In 2020, a California court ruled that use of the decimal prefixes with a decimal meaning was not misleading.[125]

IBM's first hard disk drive, the IBM 350, used a stack of fifty 24-inch platters, stored 3.75 MB of data (approximately the size of one modern digital picture), and was of a size comparable to two large refrigerators. In 1962, IBM introduced its model 1311 disk, which used six 14-inch (nominal size) platters in a removable pack and was roughly the size of a washing machine. This became a standard platter size for many years, used also by other manufacturers.[126] The IBM 2314 used platters of the same size in an eleven-high pack and introduced the "drive in a drawer" layout, sometimes called the "pizza oven", although the "drawer" was not the complete drive. Into the 1970s, HDDs were offered in standalone cabinets of varying dimensions containing from one to four HDDs.

Beginning in the late 1960s, drives were offered that fit entirely into a chassis that would mount in a 19-inch rack. Digital's RK05 and RL01 were early examples using single 14-inch platters in removable packs, the entire drive fitting in a 10.5-inch-high rack space (six rack units). In the mid-to-late 1980s, the similarly sized Fujitsu Eagle, which used (coincidentally) 10.5-inch platters, was a popular product.

With increasing sales of microcomputers having built-in floppy-disk drives (FDDs), HDDs that would fit to the FDD mountings became desirable. Starting with the Shugart Associates SA1000, HDD form factors initially followed those of 8-inch, 5¼-inch, and 3½-inch floppy disk drives. Although referred to by these nominal sizes, the actual sizes for those three drives respectively are 9.5", 5.75" and 4" wide. Because there were no smaller floppy disk drives, smaller HDD form factors such as 2½-inch drives (actually 2.75" wide) developed from product offerings or industry standards.

As of 2019[update], 2½-inch and 3½-inch hard disks are the most popular sizes. By 2009, all manufacturers had discontinued the development of new products for the 1.3-inch, 1-inch and 0.85-inch form factors due to falling prices of flash memory,[127][128] which has no moving parts. While nominal sizes are in inches, actual dimensions are specified in millimeters.

The factors that limit the time to access the data on an HDD are mostly related to the mechanical nature of the rotating disks and moving heads, including:

Delay may also occur if the drive disks are stopped to save energy.

Defragmentation is a procedure used to minimize delay in retrieving data by moving related items to physically proximate areas on the disk.[129] Some computer operating systems perform defragmentation automatically. Although automatic defragmentation is intended to reduce access delays, performance will be temporarily reduced while the procedure is in progress.[130]

Time to access data can be improved by increasing rotational speed (thus reducing latency) or by reducing the time spent seeking. Increasing areal density increases throughput by increasing data rate and by increasing the amount of data under a set of heads, thereby potentially reducing seek activity for a given amount of data. The time to access data has not kept up with throughput increases, which themselves have not kept up with growth in bit density and storage capacity.

| Rotational speed (rpm) | Average rotational latency (ms)[q] |

|---|---|

| 15,000 | 2 |

| 10,000 | 3 |

| 7,200 | 4.16 |

| 5,400 | 5.55 |

| 4,800 | 6.25 |

As of 2010[update], a typical 7,200-rpm desktop HDD has a sustained "disk-to-buffer" data transfer rate up to 1,030 Mbit/s.[131] This rate depends on the track location; the rate is higher for data on the outer tracks (where there are more data sectors per rotation) and lower toward the inner tracks (where there are fewer data sectors per rotation); and is generally somewhat higher for 10,000-rpm drives. A current, widely used standard for the "buffer-to-computer" interface is 3.0 Gbit/s SATA, which can send about 300 megabyte/s (10-bit encoding) from the buffer to the computer, and thus is still comfortably ahead of today's[as of?] disk-to-buffer transfer rates. Data transfer rate (read/write) can be measured by writing a large file to disk using special file-generator tools, then reading back the file. Transfer rate can be influenced by file system fragmentation and the layout of the files.[129]

HDD data transfer rate depends upon the rotational speed of the platters and the data recording density. Because heat and vibration limit rotational speed, advancing density becomes the main method to improve sequential transfer rates. Higher speeds require a more powerful spindle motor, which creates more heat. While areal density advances by increasing both the number of tracks across the disk and the number of sectors per track,[132] only the latter increases the data transfer rate for a given rpm. Since data transfer rate performance tracks only one of the two components of areal density, its performance improves at a lower rate.[133]

Other performance considerations include quality-adjusted price, power consumption, audible noise, and both operating and non-operating shock resistance.

Current hard drives connect to a computer over one of several bus types, including parallel ATA, Serial ATA, SCSI, Serial Attached SCSI (SAS), and Fibre Channel. Some drives, especially external portable drives, use IEEE 1394, or USB. All of these interfaces are digital; electronics on the drive process the analog signals from the read/write heads. Current drives present a consistent interface to the rest of the computer, independent of the data encoding scheme used internally, and independent of the physical number of disks and heads within the drive.

Typically, a DSP in the electronics inside the drive takes the raw analog voltages from the read head and uses PRML and Reed–Solomon error correction[134] to decode the data, then sends that data out the standard interface. That DSP also watches the error rate detected by error detection and correction, and performs bad sector remapping, data collection for Self-Monitoring, Analysis, and Reporting Technology, and other internal tasks.

Modern interfaces connect the drive to the host interface with a single data/control cable. Each drive also has an additional power cable, usually direct to the power supply unit. Older interfaces had separate cables for data signals and for drive control signals.

Due to the extremely close spacing between the heads and the disk surface, HDDs are vulnerable to being damaged by a head crash – a failure of the disk in which the head scrapes across the platter surface, often grinding away the thin magnetic film and causing data loss. Head crashes can be caused by electronic failure, a sudden power failure, physical shock, contamination of the drive's internal enclosure, wear and tear, corrosion, or poorly manufactured platters and heads.

The HDD's spindle system relies on air density inside the disk enclosure to support the heads at their proper flying height while the disk rotates. HDDs require a certain range of air densities to operate properly. The connection to the external environment and density occurs through a small hole in the enclosure (about 0.5 mm in breadth), usually with a filter on the inside (the breather filter).[135] If the air density is too low, then there is not enough lift for the flying head, so the head gets too close to the disk, and there is a risk of head crashes and data loss. Specially manufactured sealed and pressurized disks are needed for reliable high-altitude operation, above about 3,000 m (9,800 ft).[136] Modern disks include temperature sensors and adjust their operation to the operating environment. Breather holes can be seen on all disk drives – they usually have a sticker next to them, warning the user not to cover the holes. The air inside the operating drive is constantly moving too, being swept in motion by friction with the spinning platters. This air passes through an internal recirculation filter to remove any leftover contaminants from manufacture, any particles or chemicals that may have somehow entered the enclosure, and any particles or outgassing generated internally in normal operation. Very high humidity present for extended periods of time can corrode the heads and platters. An exception to this are hermetically sealed, helium-filled HDDs that largely eliminate environmental issues that can arise due to humidity or atmospheric pressure changes. Such HDDs were introduced by HGST in their first successful high-volume implementation in 2013.

For giant magnetoresistive (GMR) heads in particular, a minor head crash from contamination (that does not remove the magnetic surface of the disk) still results in the head temporarily overheating, due to friction with the disk surface and can render the data unreadable for a short period until the head temperature stabilizes (so-called "thermal asperity", a problem which can partially be dealt with by proper electronic filtering of the read signal).

When the logic board of a hard disk fails, the drive can often be restored to functioning order and the data recovered by replacing the circuit board with one of an identical hard disk. In the case of read-write head faults, they can be replaced using specialized tools in a dust-free environment. If the disk platters are undamaged, they can be transferred into an identical enclosure and the data can be copied or cloned onto a new drive. In the event of disk-platter failures, disassembly and imaging of the disk platters may be required.[137] For logical damage to file systems, a variety of tools, including fsck on UNIX-like systems and CHKDSK on Windows, can be used for data recovery. Recovery from logical damage can require file carving.

A common expectation is that hard disk drives designed and marketed for server use will fail less frequently than consumer-grade drives usually used in desktop computers. However, two independent studies by Carnegie Mellon University[138] and Google[139] found that the "grade" of a drive does not relate to the drive's failure rate.

A 2011 summary of research, into SSD and magnetic disk failure patterns by Tom's Hardware summarized research findings as follows:[140]

As of 2019[update], Backblaze, a storage provider, reported an annualized failure rate of two percent per year for a storage farm with 110,000 off-the-shelf HDDs with the reliability varying widely between models and manufacturers.[144] Backblaze subsequently reported that the failure rate for HDDs and SSD of equivalent age was similar.[7]

To minimize cost and overcome failures of individual HDDs, storage systems providers rely on redundant HDD arrays. HDDs that fail are replaced on an ongoing basis.[144][90]

These drives typically spin at 5400 rpm and include:

HDD price per byte decreased at the rate of 40% per year during 1988–1996, 51% per year during 1996–2003 and 34% per year during 2003–2010.[157][76] The price decrease slowed down to 13% per year during 2011–2014, as areal density increase slowed and the 2011 Thailand floods damaged manufacturing facilities[81] and have held at 11% per year during 2010–2017.[158]

The Federal Reserve Board has published a quality-adjusted price index for large-scale enterprise storage systems including three or more enterprise HDDs and associated controllers, racks and cables. Prices for these large-scale storage systems decreased at the rate of 30% per year during 2004–2009 and 22% per year during 2009–2014.[76]

More than 200 companies have manufactured HDDs over time, but consolidations have concentrated production to just three manufacturers today: Western Digital, Seagate, and Toshiba. Production is mainly in the Pacific rim.

HDD unit shipments peaked at 651 million units in 2010 and have been declining since then to 166 million units in 2022.[159] Seagate at 43% of units had the largest market share.[160]

HDDs are being superseded by solid-state drives (SSDs) in markets where the higher speed (up to 7 gigabytes per second for M.2 (NGFF) NVMe drives[161] and 2.5 gigabytes per second for PCIe expansion card drives)[162]), ruggedness, and lower power of SSDs are more important than price, since the bit cost of SSDs is four to nine times higher than HDDs.[16][15] As of 2016[update], HDDs are reported to have a failure rate of 2–9% per year, while SSDs have fewer failures: 1–3% per year.[163] However, SSDs have more un-correctable data errors than HDDs.[163]

SSDs are available in larger capacities (up to 100 TB)[38] than the largest HDD, as well as higher storage densities (100 TB and 30 TB SSDs are housed in 2.5 inch HDD cases with the same height as a 3.5-inch HDD),[164][165][166][167][168] although such large SSDs are very expensive.

A laboratory demonstration of a 1.33 Tb 3D NAND chip with 96 layers (NAND commonly used in solid-state drives (SSDs)) had 5.5 Tbit/in2 as of 2019[update]),[169] while the maximum areal density for HDDs is 1.5 Tbit/in2. The areal density of flash memory is doubling every two years, similar to Moore's law (40% per year) and faster than the 10–20% per year for HDDs. As of 2018[update], the maximum capacity was 16 terabytes for an HDD,[170] and 100 terabytes for an SSD.[171] HDDs were used in 70% of the desktop and notebook computers produced in 2016, and SSDs were used in 30%. The usage share of HDDs is declining and could drop below 50% in 2018–2019 according to one forecast, because SSDs are replacing smaller-capacity (less than one terabyte) HDDs in desktop and notebook computers and MP3 players.[172]

The market for silicon-based flash memory (NAND) chips, used in SSDs and other applications, is growing faster than for HDDs. Worldwide NAND revenue grew 16% per year from $22 billion to $57 billion during 2011–2017, while production grew 45% per year from 19 exabytes to 175 exabytes.[173]

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Every time you click a link to Wikipedia, Wiktionary or Wikiquote in your browser's search results, it will show the modern Wikiwand interface.

Wikiwand extension is a five stars, simple, with minimum permission required to keep your browsing private, safe and transparent.