In 1491, no European knew that North and South America existed. By 1550, Spain -- a small kingdom that had not even existed a century earlier -- controlled the better part of two continents and had become the most powerful nation in Europe. In half a century of brave exploration and brutal conquest, both Europe and America were changed forever.

The Reconquista and the origins of Spain

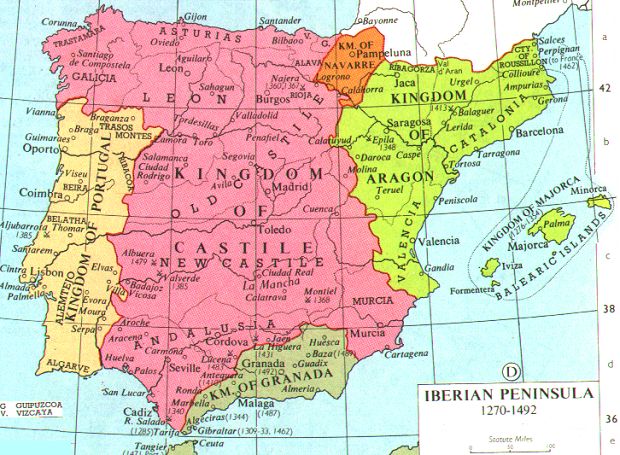

In the 1400s, "Spain" as we think of it today did not exist. The Iberian peninsula, the piece of land that juts out of southwestern Europe into the Atlantic Ocean, included three kingdoms: Aragon, a small kingdom bordering France on the Mediterranean Sea and focused on trade with Italy and Africa; Portugal on the Atlantic coast; and Castile, a large rural kingdom in the middle. The southern part of Iberia, meanwhile, was under Muslim rule, as it had been for centuries.

In the early 700s, Berbera name given by the Arabs to the North African people living in settled or nomadic tribes from Morocco to Egypt.. Muslims from North Africa, often called Moors, had conquered nearly all of the Iberian Peninsula. Over the following seven and a half centuries, the Christian kingdoms to the north gradually retook control of the peninsula, and by 1300, Muslims controlled only Granada, a small region in the south of present-day Spain. But the Reconquista, or Reconquest, was not complete until 1492. In 1479, King Ferdinand II of Aragon and Queen Isabella of Castile married, uniting their kingdoms, and thirteen years later their armies expelled the Muslims from Granada.

The Reconquista was a brutal conflict fueled in part by devotion to Christianity -- not just a war between kingdoms but a crusade against infidels. In al-Andalus -- the Arabic name for Muslim-controlled Iberia -- Christians and Jews had significant religious freedom. The Christian rulers to the north did not return the favor. The rulers of Spain's kingdoms found that their shared Christianity could unite them and set them apart from the Muslims to the south. The men who fought in the Reconquista were convinced of their superiority to their enemies who had rejected Christianity, and they developed rules of war based on that superiority -- including the right to enslave the people they conquered. Once Spain was reconquered, Muslims and Jews were forced to convert to Christianity or be expelled from Spain.

The long Reconquista tended to make the Spanish, and especially Castilians, not only strongly devoted to Christianity but militaristic and romantic. Castile was an agricultural society based on personal relationships, in which a person's reputation and honor were tremendously important. One historian writes that -

Castilian men were tough, arrogant, quick to take offense, undaunted by danger and hardship, and extravagant in their actions. They would suffer hunger, hardship, extremes of climate, and still fight savagely against great odds....Sixteenth-century Spaniards were fascinated with herioc stories, the adventures of perfect knights, ceremonious and courtly behavior, and strange and magical happenings.

1

Finally, the Reconquista was driven by a desire for land and profit. Because kings in the Middle Ages were not as strong or as wealthy as they would later become, most military actions against the Moors were privately financed. Leaders of armies, since they had risked their own money, won rights to conquered land and a share of conquered peoples' wealth.

The reconquerers, in short, were the perfect men to cross a dangerous ocean and conquer a "New World" of dense uncharted forests, tropical diseases, and hostile heathens. They were devoted to God, king, and queen; they were tough; and they were eager for wealth and glory. And after 1492, with the Reconquista complete, they were in the market for a new crusade. Conveniently enough, Christopher Columbus gave them one.

Into the "New World"

In the late Middle Ages, Europeans were fascinated with the idea of Asia and its wealth. Europeans and East Asians had long known of each other -- Alexander the Great's empire had connected Greece and India in the fourth century BCE, and later, the Han Dynasty of China and the Roman Empire traded regularly and exchanged a few diplomats. During the Middle Ages, though, trade and travel between Europe and Asia stopped almost entirely.

The Crusades, in which Europeans fought to retake the Holy Land from Muslims, brought them into contact with eastern cultures for the first time in centuries. They wanted spices, silks, jewels, gold, and other luxury goods from China, India, and the East Indies -- the islands southeast of the Asian continent, including the modern nation of Indonesia. But east Asia lay thousands of miles away, across vast deserts and the Himalaya Mountains, and the road from Europe to China was controlled by foreign rulers and by middlemen who charged money to pass the goods along. As a result, by the time spices and other goods reached Europe, they were extremely expensive.

Portugal, which had completed its own Reconquest in the thirteenth century, was the first European nation to try to trade directly with Asia. Under Prince Henry "the Navigator," the Portuguese began to explore the west coast of Africa. In 1488 Bartolomeu Dias sailed all the way around the southern tip of Africa, the Cape of Good Hope, proving that there was an ocean route around the continent. In 1497, Vasco da Gama followed Dias' route, then sailed north and east to India -- opening up the riches of Asia to Portugal.

Columbus' great mistake

In 1492, Christopher Columbus, a sailor from Genoa (then an independent city-state in northern Italy), convinced Isabella and Ferdinand to finance a voyage across the Atlantic to Asia. Although it was widely accepted in Europe by this time that the earth was round, scholars disagreed about the size of the globe. Columbus argued that the riches of China and the East Indies lay only 2,400 miles to the west of Spain -- making the Atlantic Ocean about the width of the Mediterranean Sea -- but most others said it was much farther.

For years, Columbus failed to persuade England, Portugal, Spain, Genoa, and Venice to give him ships and men. Finally, the new monarchs of reconquered Spain, eager for new sources of wealth and opportunities to spread Christianity, decided to give him a chance. They named him governor of any new lands he discovered and promised him a ten percent share in their wealth, sent him to sea -- and, quite possibly, expected never to see him again.

Columbus was wrong, of course -- bold enough to sail thousands of miles into uncharted waters, but completely mistaken in his geography. Asia lies more than 12,000 miles west of Europe, and had the Americas not been waiting in the middle, Columbus would never have reached land. He reached the Bahamas instead, more or less where he thought the East Indies should have been, and after three more voyages to the Caribbean and the coast of South America he died in 1506 still believing he had been exploring mainland Asia. But Columbus' incredible (and lucky) mistake turned out to be one of the most important events in the history of human civilization.

The "Columbian exchange"

The world's two great land masses -- North and South America in the western hemisphere and Europe, Asia, and Africa in the eastern hemisphere -- had been isolated from each other for 10,000 years. When the land bridge across the Bering Strait closed after the last Ice Age, the Paleoindians of the Americas and their Stone Age counterparts in Asia were cut off. In the hundreds of thousands of years before that, the two halves of the world had evolved different animals, plants, and microbes.

Over the millenia, the human inhabitants of the "old" and "new" worlds developed vastly different cultures, languages, and religions; they found different ways of adapting to their different envinronments; and their bodies over hundreds of generations became resistant to the diseases of their different worlds. When the two great land masses were rejoined by European exploration, the resulting exchange of people, crops, animals, ideas, and diseases -- called the "Columbian exchange" -- changed both worlds forever.

The Vikings briefly settled Greenland and parts of eastern Canada in about 1000 CE. But they didn't stay long, and they didn't spread word of their discovery in Europe. There are also theories that Chinese explorers found the west coast of North America sometime before Columbus' journey, but if the stories are true, the Chinese, like the Vikings, returned home without making an impact on either continent.

Conquest by sword and germs

Immediately, the Spanish set about conquering the world they had discovered. Within a hundred years this small European nation had claimed the better part of two continents. They relied on a combination of military superiority, occasional diplomacy, luck -- and their greatest ally, disease. Then, convinced that the peoples of the Americas were uncivilized heathens, they set about destroying much of what they found.

The Caribbean

Columbus easily dominated the peoples of the Caribbean, who were for the most part friendly and peaceful. They practiced advanced agriculture, traded extensively among the islands, and had a great deal of leisure time. Columbus, believing he was off the coast of India, called them "Indians" and hoped they would be faithful subjects of Ferdinand and Isabella. But faithful subjects, to Columbus, would convert to Christianity and grow crops that would make money for Europeans. In his journal, he wrote,

It seemed to me that they were a people who were very poor in everything. They go as naked as their mothers bore them, even the women, though I only saw one girl, and she was very young. All those I did see were young men, none of them more than thirty years old.... They do not carry arms and do not know of them, because I showed them some swords and they grasped them by the blade and cut themselves out of ignorance.... They ought to make good slaves for they are of quick intelligence, since I notice that they are quick to repeat what is said to them, and I believe that they could very easily become Chirstians, for it seemed to me that they had no religion of their own. God willing, when I come to leave I will bring six of them to Your Highnesses so that they may learn to speak...

2

To a European, a "civilized" person was someone who lived in a house, ate his meals at a table -- and, certainly, wore full clothes! These nearly naked people with no understanding of metal weapons must have seemed incredibly primitive to Columbus and his men -- like something, perhaps, out of the Garden of Eden. If the people of the "Indies" were so poor and uncivilized, Columbus believed he had every right to take their land and make them into "servants."

Slavery and smallpox

On Hispañola (present-day Haiti and the Dominican Republic), Columbus tried to enslave the indigenous Taino people to grow plant sugar cane, but an epidemic of smallpox and other diseases wiped out the entire native population of the island -- as many as two million people.

Smallpox was endemic to Europe and Asia -- it was common there, and over thousands of generations people had built up a resistance to it. Even so, it was a fast-spreading, deadly disease. As late as the eighteenth century, hundreds of thousands of Europeans died of smallpox each year.3 But smallpox had never existed in the Americas, and Native Americans had no immunity to it at all.

With the native population gone, the Spanish began to import slaves from Africa to grow their sugar cane -- beginning an institution that would create misery and profit in the Americas for almost 400 years.

Mexico

In 1519 Hernán Cortés arrived in Mexico from Cuba with 11 galleons, 550 men, and 16 horses -- the first horses on the American continent. Within two years his conquistadores, conquerors, had won control of the Aztec kingdom that spanned most of present-day Mexico and Central America.

The Aztec empire, unlike the small tribes that dotted the Caribbean -- and more than a little like Spain -- was a complex state built on military conquest. Its emperor Moctezuma ruled with an iron fist from the great Aztec capital at Tenochtitlán. It seems incredible that so few men could conquer so great an empire, but its centralized authority -- its vast territory was ruled by one man from a single city -- actually made it easier to conquer. Once the capital was taken and the emperor captured, the entire empire fell under Spanish control.

Of course, the conquistadores had other advantages -- some of them accidental. One of Cortés' soldiers had smallpox, and he started an epidemic that killed a third of the population of the Aztec empire.

The Aztecs may also have mistaken Cortés for the deity Quetzalcoátl, or Plumed Serpent, who according to prophesy would return from the east to reclaim his kingdom -- perhaps in 1519. When Cortés arrived -- from the east, with fair skin, riding four-legged creatures never before seen in Mexico, wearing shining armor and looking for all the world like someone who wanted to reclaim a kingdom -- Moctezuma feared that he might be Quetzalcoátl and did not immediately meet him in battle. The delay gave Cortés the time he needed to get a foothold.

South America

Like the Aztecs of Mexico, the Incas of Peru controlled a vast empire with great riches, including the gold and silver the Spanish desperately wanted. The Incas maintained their power by forcing conquered peoples to adopt their language and religion. To manage their empire, they built a network of roads through the Andes mountains.

Also like the Aztecs, the Incas fell quickly to the Spanish. Francisco Pizarro landed in Peru in 1530, and his small army with their steel weapons, armor, and horses dominated the Incas in battle. Disease had already spread south from Mexico and weakened the Inca people. Pizarro captured the Inca emperor, Atahualpa, and quickly took control of the empire. Within a few decades, the Spanish controlled most of South America.

Blood and gold

What Cortés and his men saw in Tenochtitlán horrified them. The many Aztec gods demanded human sacrifice -- to ensure that the sun would coninue to rise in the morning, to grant fertility, or to guarantee a good harvest. The Aztecs fought wars with neighboring peoples to capture victims for sacrifice. In the most famous ritual, the victim was spread-eagled on a round stone atop a great pyramid while a priest cut out his heart and offered it, still beating, to the god Huitzilopochtli.

The Spanish, more convinced than ever of their superiority, forced most of the people of Mexico to convert to Christianity. Priests burned Aztec books and destroyed idols and temples. Indigenous people were enslaved to work in gold mines. Disease reduced the population of Mexico from more than 20 million when Cortés arrived in 1519 to about 2 million by 1600.

Meanwhile, the gold and other riches sent home to Spain financed one of the most powerful empires in the history of the world. Spanish monarchs used this wealth to fight a series of religious wars in Europe, including the attempted invasion of England by the Spanish Armada. By the 1600s, Spain was easily the most powerful kingdom in Europe.

Bartoleme de Las Casas, a Spanish priest who witnessed the worst of Spanish cruelty, had this to say in 1542 about the conquest of Mexico and the Caribbean:

Into this sheepfold, into this land of meek outcasts there came some Spaniards who immediately behaved like ravening wild beasts, wolves, tigers, or lions that had been starved for many days. And Spaniards have behaved in no other way during the past forty years, down to the present time, for they are still acting like ravening beasts, killing, terrorizing, afflicting, torturing, and destroying the native peoples, doing all this with the strangest and most varied new methods of cruelty, never seen or heard of before, and to such a degree that this Island of Hispaniola once so populous (having a population that I estimated to be more than three million), has now a population of barely two hundred persons....

As for the vast mainland [Mexico]... We can estimate very surely and truthfully that in the forty years that have passed, with the infernal actions of the Christians, there have been unjustly slain more than twelve million men, women, and children. In truth, I believe without trying to deceive myself that the number of the slain is more like fifteen million....

Their reason for killing and destroying such an infinite number of souls is that the Christians have an ultimate aim, which is to acquire gold, and to swell themselves with riches in a very brief time and thus rise to a high estate disproportionate to their merits. It should be kept in mind that their insatiable greed and ambition, the greatest ever seen in the world, is the cause of their villainies. And also, those lands are so rich and felicitous, the native peoples so meek and patient, so easy to subject, that our Spaniards have no more consideration for them than beasts. And I say this from my own knowledge of the acts I witnessed. But I should not say "than beasts" for, thanks be to God, they have treated beasts with some respect; I should say instead like excrement on the public squares....

The Indians began to seek ways to throw the Christians out of their lands.... And the Christians, with their horses and swords and pikes began to carry out massacres and strange cruelties against them. They attacked the towns and spared neither the children nor the aged nor pregnant women nor women in childbed, not only stabbing them and dismembering them but cutting them to pieces as if dealing with sheep in the slaughter house. They laid bets as to who, with one stroke of the sword, could split a man in two or could cut off his head or spill out his entrails with a single stroke of the pike. They took infants from their mothers' breasts, snatching them by the legs and pitching them headfirst against the crags or snatched them by the arms and threw them into the rivers, roaring with laughter and saying as the babies fell into the water, "Boil there, you offspring of the devil!" Other infants they put to the sword along with their mothers and anyone else who happened to be nearby. They made some low wide gallows on which the hanged victim's feet almost touched the ground, stringing up their victims in lots of thirteen, in memory of Our Redeemer and His twelve Apostles, then set burning wood at their feet and thus burned them alive. To others they attached straw or wrapped their whole bodies in straw and set them afire. With still others, all those they wanted to capture alive, they cut off their hands and hung them round the victim's neck, saying, "Go now, carry the message," meaning, Take the news to the Indians who have fled to the mountains. They usually dealt with the chieftains and nobles in the following way: they made a grid of rods which they placed on forked sticks, then lashed the victims to the grid and lighted a smoldering fire underneath, so that little by little, as those captives screamed in despair and torment, their souls would leave them.

4

Las Casas spent most of his life fighting for the indigenous peoples of Central and South America. He tried to build a settlement on the coast of Venezuela with farmers rather than soldiers, worked to convert indigenous peoples by peaceful means, and argued for the abolition of Indian slavery. His descriptions of the conquest horrified King Charles V and his advisors, and the government agreed to limit the use and ownership of slaves -- until colonists in Peru threatened to revolt. Las Casas was never able to gain the fair treatment of Central and South American Indians, but for his efforts he is remembered today as one of the earliest proponents of human rights.

- 1. Hudson, Charles, Knights of Spain, Warriors of the Sun: Hernando de Soto and the South's Ancient Chiefdoms (Athens, Ga.: The University of Georgia Press, 1997), 8.

- 2. Columbus, Christopher and B. W. Ife (translator), Journal of the First Voyage (Diario del Primer Viaje) (Warminster, England: Aris & Phillips Ltd.), 29–31.

- 3. Barquet, Nicolau and Pere Domingo, “Smallpox: The Triumph over the Most Terrible of the Ministers of Death,” in Annals of Internal Medicine 127:8 (1997).

- 4. de Las Casas, Bartoleme and Herma Briffault (translator), The Devastation of the Indies: A Brief Account. (New York: Seabury Press, 1974), 39–44.