Explore more from In Their Own Words

In Their Own Words: Sergeant James Thurlby

Related topics

James Thurlby (left) with two of his friends, Norfolk, 1943

A man of letters

James Thurlby was born in Wortley, Yorkshire, on 8 February 1920. He was educated at King Edward VII School in Sheffield. It was here, we may presume, that he began to cultivate his lifelong passion for writing.

When his father died in 1938, James moved to Rotherham, where he worked as a journalist on a local newspaper.

In February 1940, following the outbreak of the Second World War, he signed up to serve in the Royal Navy. He was discharged a few months later, but soon switched to the Army, joining the Coldstream Guards.

Review of the Guards Armoured Division, Salisbury Plain, 16 April 1942

Guards Armoured Division

Thurlby became a member of the regiment's newly raised 5th Battalion. This unit was assigned to the Guards Armoured Division, an elite mechanised force composed of elements from all the regiments of Foot Guards.

The Guards Armoured Division had been created in May 1941 to combat an anticipated invasion of the British Isles. When this threat subsided, the Division remained in Britain and was held in readiness to form the spearhead of an eventual cross-Channel invasion of Nazi-occupied Europe.

No 2 Company, Training Battalion, Coldstream Guards, October 1944 (Thurlby is third from the right in the centre row)

Normandy

Immortalised as 'D-Day’, this invasion finally began on 6 June 1944. In the greatest amphibious operation ever mounted, a vast multinational force assaulted the beaches of Normandy in north-west France. Despite some setbacks and bloody fighting, the initial landings were a great success and the Allies swiftly secured a strong foothold.

The next phase of the campaign proved far more difficult. The Allies were drawn into a gruelling battle of attrition as they attempted to break out from their Normandy beachhead. Operating on the left flank, the British Army became embroiled in a bitter struggle for the city of Caen. Here, it would experience some of the most intense fighting in its history.

Mobilisation

The Guards Armoured Division arrived in Normandy at the end of June and was swiftly sent into battle. It first saw action at Carpiquet to the west of Caen, where it encountered the fanatical fighters of the 12th SS Panzer Division 'Hitlerjugend' (Hitler Youth). It then took part in Operation Goodwood, the British Army’s largest ever armoured assault.

Thurlby's unit was mobilised on 12 June. At this time, he began keeping a rough diary. His early entries note an infectious feeling of levity among the men. However, this soon gave way to a more sombre mood as the prospect of fighting drew near.

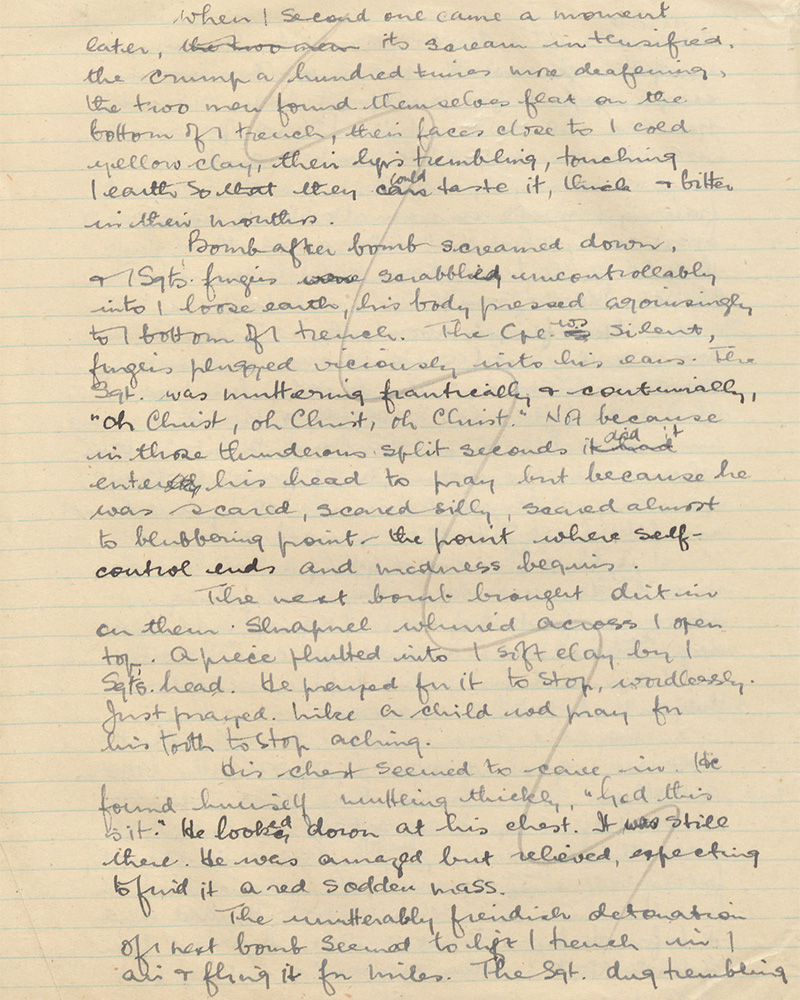

Handwritten notebook containing diary extracts by Sergeant James Thurlby, 1942-45

‘How shall we fare? Who will come back? Shall we all come through? Or will some lie out there stiff and cold beneath a foreign sky? What Goddam miserable thoughts. I wonder why I write this.’

James Thurlby, diary entry - 17 June 1944

Artillery fire

Thurlby’s battalion landed at St Aubin-sur-Mer and was deployed to the line on 28 June. Any lingering notions that war could be glorious or romantic were soon dispelled as he suddenly faced its grim reality.

The horror and fear of being under fire soon began to take a heavy toll, revealed in a particularly harrowing account of an artillery bombardment near St Manvieu on 3 July.

Thurlby was not alone in feeling like this. The Coldstream Guards regimental history recorded that more men collapsed from nervous strain in this period than in any other during the campaign.

‘The whine of the first one found Frank and I sitting up in the trench. The crump of the second put us flat on our faces on the bottom chewing earth. I don’t know what Frank was saying but I was muttering frantically, continuously, “Oh Christ, oh Christ, oh Christ.” Not because it had entered my head to pray, but because I was scared out of my wits, scared silly, scared almost to blubbering point. My fingers digging and scrabbling in the loose yellow soil at the bottom of the hole.’

James Thurlby describing being under artillery fire at St Manvieu - 3 July 1944

Ruined centre of the city of Caen, 1944

Death and destruction

In his diary, Thurlby paints a bleak picture of the devastated towns and countryside. Of St Manvieu, he wrote: ‘The village is crumbling to a smouldering desolate ruin before our eyes.’

More distressing was the gruesome sight of the war dead. On 6 July, he came across the mangled corpses of three Germans in a dugout. The men had clearly been taken by surprise and were only half dressed when they were killed.

Thurlby undertook the nauseating task of searching two of the bodies for identification. It turned out that the men were aged just 19 and 21. The job was made even more upsetting by the discovery of a cache of love letters and a picture of a girlfriend that one of the soldiers had been carrying.

‘One was clothed solely in his trouser which he had only had time to pull as far as his knee. His left hand was a jellied mass of shredded flesh. There was a hole in his head from which thick purplish blood had oozed and clotted over his face.’

James Thurlby describing a dead German soldier that he encountered in Normandy - 6 July 1944

British soldiers in position near Caen, July 1944

Wounded in action

As his unit was being deployed for action for Operation Goodwood, Thurlby sustained a wound to the hand.

He was fortunate to catch a ‘blighty’ one – an injury serious enough to require evacuation home, but not to leave him disabled or disfigured. However, it was with mixed feelings that he left the front, with his relief tempered by sadness at the thought of the comrades he was leaving behind.

‘I cannot write about it. It was all too sudden and unexpected and strange. I know there was blood and the interior of an ambulance – white, strained faces full of pain and tiredness – and suddenly I too felt very tired and sick.’

James Thurlby recounting his wound - 19 July 1944

Home Front

Back in Britain, Thurlby found life hard. He was exasperated by the accounts of warfare he read in the media, which he found grossly misleading. Also frustrating was the general public's ignorance of the realities of war, and the complacency he encountered from those who felt that the success of D-Day meant the war was already won.

‘I am convinced that a certain percentage of the population are scarcely conscious of the fact that there is a war on at all and an even larger percentage have settled into such a stage of torpidity as to believe that now is the time to sit back and say: “The war is over.”’

James Thurlby on war apathy - 25 August 1944

War journalist

Encouraged by his comrades, Thurlby took to writing to vent his feelings and educate the public. Securing a job with the Guards Division’s regimental press officer, he returned to the front in January 1945 to report on the war.

Accompanying the Division as it advanced into the heart of Nazi Germany, he wrote a series of powerful articles, laying bare the horrors of the conflict and extolling the heroism of the men who fought in it.

Throughout this time, he kept up his diary, recording in increasingly emotive and unguarded language the sights, sounds and stench of war.

‘I have been through hell. My best friends have been killed. I have seen death, mutilation, carnage and madness in all their crudest, most horrible forms.’

James Thurlby, diary entry - 25 August 1944

Fallen comrades

As the fighting continued, news gradually came through that, one by one, his close comrades had been killed. In his diary, Thurlby railed against the evil of war, and the misery and desolation it brings.

James Thurlby (left) with two of his close comrades, Jim ‘Sweeney’ Todd and John Whaley, both of whom were killed in the war, 1943

‘You are branded with bitterness and the bitterness will never leave your heart, not in a lifetime. You know everything is unfair and unjust and war is the filthiest man-created, Godless state there ever was, is or can be.’

James Thurlby describing the impact of losing a comrade - 25 August 1944

An unfinished work

Thurlby remained in Germany at the end of the war, reporting on its aftermath. In 1948, he moved to Dublin with his wife, Anne. Here, he worked as a reporter for 'The Irish Times' and enrolled at Trinity College to read Philosophy, graduating in 1952.

During his time in Dublin, he reworked his wartime diary into a typescript in preparation for publication. However, he never completed this project. Perhaps it was too personal. Or perhaps he was discouraged by a conviction that people were tired of hearing about war.

‘So perhaps this book which I have tried to compile will come too late. Perhaps the message which I have tried to convey, the message which on re-reading these entries I seem to find remarkably clear, is one which after all no one will particularly want to read... The diary will lay moulding in a drawer or case, and the feelings of gallant men midst fear and death over six long years will be forgotten “because the people’s sick of war”.’

James Thurlby reflecting on his diary in the final entries - 3 May 1945

Later life

After returning to England in 1954, Thurlby took up a post in the Public Relations Department of Imperial Chemicals in London. In 1959, he bought a house in Surrey, where he remained for the rest of his life. Anne sadly died in 1963, aged just 42.

Thurlby re-married in 1968. He continued to write and had several articles and short stories published, some of which were broadcast on the BBC. He died in November 2002.

A digitised version of his wartime diary is available to access via our Online Collection.

Access to the Archive

The National Army Museum provides public access to its library and archival collections via the Templer Study Centre. Over the coming weeks and months, we will be sharing more stories across our website and social media channels, highlighting some of the valuable personal insights these collections hold.